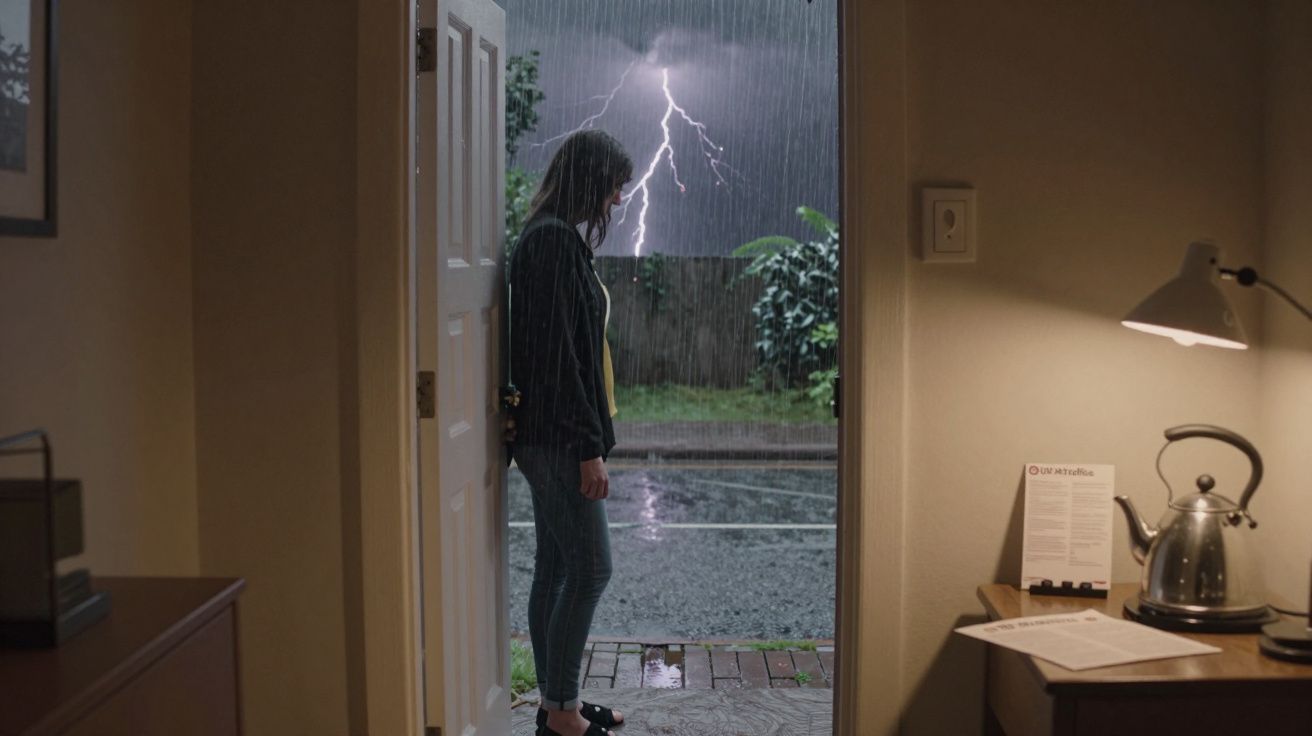

Thunder over the terraces, the smell of wet tarmac, the streetlights flickering a little too often. In countless British homes, that’s the cue: someone puts the kettle on, someone else pads over and leans in the front doorway to “watch the show”.

You can picture it: one hand on the frame, one foot half outside on the step, shoulder against the brickwork. The rain whips sideways, a bright flash turns the cul‑de‑sac white for a heartbeat, and from the hall comes the same line families have passed down for years: “Stay in the doorway, it’s the safest place.”

Meteorologists and lightning engineers will tell you the opposite.

That threshold - half in, half out, touching the building - is one of the most dangerous spots you could choose.

The UK Met Office, the Royal Meteorological Society and safety bodies like RoSPA all boil it down to a blunt rule: get fully indoors, stay away from openings, or get inside a proper vehicle. Yet every summer, A&E departments treat people injured in porches, doorways and at open windows.

This isn’t about being afraid of weather. It’s about understanding how electricity actually travels when it has ten million volts to spend.

The cosy doorway myth that refuses to die

Doorways feel safe because they feel solid. There’s a frame, a lintel, a clear line between “inside” and “outside”. In older stone houses that frame might even have been the strongest bit of the wall, the place you were told to stand in an earthquake.

Lightning doesn’t care about our sense of boundaries. It cares about conductors, moisture and differences in voltage. Lightning safety isn’t about feeling sheltered; it’s about where electricity can travel.

A modern front door often sits in a frame tied into metal lintels, damp masonry and the house’s wiring. The porch may carry a gutter or a bit of metal roofing. Outside, rainwater and paving stones form a wet, conductive skin across the ground. When lightning strikes nearby, those paths can all link up.

An open doorway also punches a hole in your “safe shell”. You are literally standing in the gap that separates indoor electrics from the charged air outdoors. That’s exactly where lightning is most likely to jump, or “side‑flash”, if it’s looking for a shorter route to earth.

What actually happens when lightning hits near your front door

We tend to imagine lightning as a single, neat bolt that either hits you or it doesn’t. Reality is messier and more dangerous.

When a strike hits a roof, tree, chimney, lamp post or the road outside, several things can happen at once:

Side flash from nearby structures

If lightning hits a gutter, drainpipe, porch roof or nearby tree, part of the current can jump sideways through the air to something - or someone - at a different voltage. Leaning on a damp doorway frame makes you an attractive target.Ground current and “one foot in, one foot out”

Electricity spreads out through the ground after a strike. If your feet are at different distances from where it hit, the voltage at each foot can be wildly different. With one foot on a wet step and the other on a drier floor inside, your body becomes the bridge between those voltages.Currents travelling through the building fabric

Damp brick, steel lintels, wiring and pipework can all carry a surge. Touching the door frame, letterbox, keys in the lock, or even a radiator right by the door plugs you straight into that path.

Lightning doesn’t need a direct hit to hurt you; it just needs a path that includes you.

The classic doorway stance - hand on the frame, shoulder on the wall, feet apart on different surfaces - quietly lines up several of those risks at once.

Three safer spots UK forecasters actually recommend

UK weather services keep repeating the same simple hierarchy. No place outdoors is completely safe in a thunderstorm, but some choices are far better than others.

1. Well inside a substantial building

Not a tent, not a beach hut, not a metal bus shelter - a proper building with wiring and plumbing.

Once you’re in:

- Move away from doors, windows, fireplaces and external walls.

- Avoid taps, baths, showers and sinks while thunder is audible; plumbing can conduct strikes.

- Stay off corded landlines and try not to lean on big appliances or radiators.

- Unplug non‑essential electronics if you can do it before the storm is overhead.

The rough Met Office rule of thumb is the 30/30 rule: if the gap between flash and thunder is under 30 seconds, get inside; wait 30 minutes after the last thunder before resuming normal outdoor activities.

2. Inside a fully enclosed metal‑topped vehicle

If there’s no building nearby, UK guidance is clear: a car with a solid roof is the next best option.

- Get into a hard‑topped car or van, not a convertible, golf cart or bike shelter.

- Close windows and doors, and avoid touching the metal frame, steering wheel, gearstick or radio.

- If lightning hits, the metal shell channels current around you and into the ground - a sort of moving Faraday cage.

It may feel counter‑intuitive when you’re surrounded by glass, but statistically you’re far safer inside a closed car than standing just outside it under the boot lid.

3. If you are stuck outside with nowhere to go

Sometimes, on a fell, a beach or an open field, there simply isn’t a building or a vehicle you can reach in time. UK services frame this as “less dangerous, not safe” - but it’s still worth downgrading the risk:

- Get to a low, open spot, away from hilltops, ridges, cliff edges and the highest ground.

- Stay well clear of isolated trees, telegraph poles, flagpoles, fences, goalposts, lakes and rivers.

- If you’re in a group, spread out by several metres so one strike can’t affect everyone at once.

- Crouch with your feet together, heels touching, as low as you can without lying flat, and minimise contact with the ground. A rucksack or rolled‑up jacket under your feet can slightly reduce ground current passing through your body.

If you can see lightning and count fewer than ten seconds before you hear the thunder, you are well within striking range. The priority then is to stop moving around and get into the “smaller target, single contact point with the ground” position until the worst passes.

Doorways, windows and sheds: the places to avoid

Certain spots feel intuitively cosy but show up again and again in lightning‑injury reports.

Steer clear of:

- Doorways and open porches – classic side‑flash and step‑voltage traps.

- Open windows, patio doors and French doors – flying glass and side flashes if frames or nearby structures are struck.

- Balconies and roof terraces – elevated, exposed and often with metal railings.

- Garden sheds, beach huts, tents and gazebos – too flimsy to act as proper lightning protection.

- Leaning under isolated trees or metal shelters – the tree or frame may take the main hit; you share the current flowing away.

Here’s a quick comparison for common “storm‑watching” spots:

| Place you might stand | How safe it really is | Why |

|---|---|---|

| Front doorway / open porch | High risk | Side flashes, ground current, contact with building fabric |

| Middle of a room, away from openings | Low risk indoors | The building shell carries most of the current around you |

| Inside a hard‑topped car, windows shut | Low to moderate risk | Metal body works like a Faraday cage if you don’t touch it |

| Under a lone tree in a field | Very high risk | Trees attract strikes; current spreads through trunk, roots and ground |

Why we keep picking the worst place

Part of this is habit. Many of us grew up with relatives who watched storms from the front step and “were fine”. Survivorship bias is powerful: we remember the dozens of harmless evenings, not the physics behind the near‑misses.

There’s also something deeply human about standing on the threshold - neither fully in nor fully out - to stare at the sky. It feels like being brave but not reckless. We remember the times nothing happened, not the odds we quietly rolled.

Scientists and forecasters talk in probabilities and pathways, which rarely go viral. By contrast, a neighbour saying “Doorways are safest, my grandad always said so” is simple, vivid and comforting. The job of modern guidance is to be just as simple without being wrong.

If you still want to enjoy the drama, do it like the pros: stand well back from the windows, let the lights flicker, and keep the awe without the extra risk.

A lightning‑safety cheat sheet

When thunder arrives, these quick rules line up with UK weather‑service advice:

Do:

- Get inside a substantial building or hard‑topped vehicle as soon as you hear thunder.

- Follow the 30/30 rule to decide when to go in and when it’s safer to come out.

- Stay away from windows, doors, fireplaces, taps and showers.

- Postpone outdoor sports, swimming, boating, climbing and golf.

Don’t:

- Stand in doorways, on balconies, under porches or in open garages to watch the storm.

- Shelter under isolated trees, pylons, masts or small open structures.

- Use corded landlines or touch plugged‑in electronics while the storm is overhead.

- Lie flat on the ground if you’re caught outside; crouch instead.

Think of it this way: your house or car is the safe shell. Doorways, open windows and porch steps punch holes in that shell at exactly the moment you need it intact.

FAQ:

- Is it ever safe to stand in a doorway during a thunderstorm? From a lightning perspective, no. Modern safety advice is clear: move well away from doors and windows and deeper into the building.

- Are rubber‑soled shoes enough to protect me? Not against lightning. The voltages involved are so huge that ordinary footwear makes little difference to a nearby strike.

- Can lightning really travel through plumbing and wiring? Yes. Metal pipes, cables and even damp masonry can all carry part of a lightning surge, which is why taps, showers and corded phones are on the avoid list.

- Is it safe to watch lightning through a window? It’s much safer than being outside, but still better to stand a little back from large panes and metal frames in case of side flashes or shock waves.

- How far away does a storm need to be before I can go back outside? UK guidance generally uses the 30‑minute rule: wait half an hour after the last clap of thunder before resuming outdoor activities, as dangerous strikes can occur on the trailing edge of a storm.

Comments (0)

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!

Leave a Comment